The View Transitions API, the Navigation API and the SPA vs MPA debate

There’s been an often contentious SPA vs MPA debate for as long as I can remember. Two new browser APIs are set to change the debate.

The Navigation API

Here’s what happens by default when you click a link in a regular website:

The browser navigates to the new page, the page loads, the title of the page changes in the browser’s tab, focus is on the body, and if you’re using a screen reader, the software announces the title of the page.

If you press the back or forward button, the browser will automatically restore the scroll position so that you don’t have to re-scroll from the top of the page.

In a SPA, a client-side router has to reimplement what web browsers provides out of the box. Client-side routers are built using the History API. The Navigation API is a modern replacement.

The Navigation API is part of the HTML specification. It’s been available in Chrome and Edge since version 102. Firefox has expressed a positive position on the standard.

- Safari position on Navigation API (no position yet)

- Firefox position on Navigation API (positive)

The navigate event occurs whenever a navigation is going to happen — when a user clicks a link, when a form is submitted, etc.

navigation.addEventListener('navigate', (event) => {

event intercept ({

async handler() {

// Fetch the content and modify the DOM here

}

});

});

The Navigation API readme is a great writeup explaining the issues the API is trying to fix:

“With cross-document navigations, accessibility technology will announce the start of the navigation, and its completion. But traditionally, same-document navigations (i.e. single-page app navigations) have not been communicated in the same way to accessibility technology.”

Client-side routers built with the History API have typically made use of aria-live regions to fill-in here. This is simplified by the Navigation API:

“Any navigation that is intercepted and converted into a single-page navigation using

navigateEvent.intercept()will be communicated to accessibility technology in the same way as a cross-document one.”

Similarly, focus is also brought into closer parity with cross-document navigation, as any navigation intercepted by navigateEvent.intercept() will set focus on the <body> element by default (or on the first element with the autofocus="" attribute, if there is one).

Scroll management is also simplified.

Browser-native loading spinner

During cross-document navigations, the browser will automatically show a loading indicator in place of the favicon in the tab. This is a nice and consistent way to let the user know that something is happening. SPAs have, until now, had no way to tap into this behaviour. The Navigation API brings the ability to activate this native browser loading spinner, rather than needing to implement your own within the page.

Cross-document navigations have improved

Since the time SPAs originally became popular (circa 2013), the experience of cross-document navigation has markedly improved. In what have retroactively been called Multi-Page Applications (previously known as regular websites built with HTML), there used to be a jarring flash of white whenever a user clicked a link. That was the primary reason why frontend routing originally became popular. In 2019, Chrome implemented paint holding. Safari has done paint holding for years. When you click a link, the browser continues to show the current page briefly until the next one loads. Due to paint holding, if a website is fast enough, cross-document navigations are often indistinguishable from SPA navigations.

Another advancement is bfcache, which only works for cross-document navigation. Due to bfcache, which is supported in all browsers, pages load instantly when using the browser’s back and forward buttons.

While they don’t yet have full browser support, prefetching and prerendering can also help bring the performance of cross-document navigations closer to that of SPAs.

The View Transitions API

The View Transitions API is a way to animate between states when you make changes to the DOM.

document.startViewTransition(() => updateDOM(data));

It captures a screenshot of the current state and a screenshot of the new state and animates between the two. You can use it for all sorts of things (sorting a list, for example), but animating page navigations is the most notable use case.

The View Transitions API works for SPA navigations in Chrome and Edge. Safari and Firefox have both expressed positive positions on the standard.

You can also use View Transitions on websites that don’t make use of a client-side router by placing a <meta> tag in the <head> of the page (this is currently experimental, only implemented in Chrome Canary, and might have its own drawbacks):

<meta name="view-transition" content="same-origin" />

View Transitions are already integrated into Svelte, Astro and Nuxt.

Will the View Transitions API kill SPAs?

Some people seem to think so. Here’s Jeremy Keith:

“Their bucketloads of JavaScript wouldn’t be needed if navigation transitions were available in browsers”

And here’s Alex Russell:

“Page Transitions are incredibly important. We need to get away from “SPA” as the default style of building on the web; it has been an unmitigated disaster.”

Animated page transitions were never the main reason SPAs became popular. The vast majority of SPAs do not have page transitions, and they’re hard to implement with most JavaScript frameworks (Svelte seems to be the exception). However, the benefit of View Transitions doesn’t just lie in animation. Here’s Fred K Schott, the creator of Astro:

“Transitions and animations are fun to demo, but personally for me it’s more about having persistent UI across page loads and what that unlocks. The native app shell “feel” but without the JS.”

Performance

The React core team have made the admission that the much-touted benefits of SPAs come with some severe drawbacks. For many years the React documentation officially recommended Create React App. It is now a dead project. Dan Abramov has written of the issues with this client-side only approach:

“By design, Create React App produces a purely client-side app. This means that every app created with it contains an empty HTML file and a

<script>tag with React and your application bundle. When the empty HTML file loads, the browser waits for the React code and your entire application bundle to download. This might take a while on low-bandwidth connections, and the user does not see anything on the screen at all while this is happening. Then, your application code loads. Now the browser needs to run all of it, which may be slow on underpowered devices. At last, at this point the user sees something on the screen — but often you’ll also need to load some data. So your code sends a request to load some data, and the user is waiting for it to come back. Finally, the data loads, the components re-render with the data, and the user sees the final result.This is quite inefficient, though it’s hard to do better if you run React on the client only. Compare this to a server framework like Rails: a server would start the data fetch immediately, and then generate the page with all the data. Or take a static build-time framework like Jekyll that does the same, but during the build, and produces an HTML+JS+CSS bundle you can deploy to a static hosting. In both cases, the user would see the HTML file with all the information instead of a blank file waiting for the scripts to load. HTML is the cornerstone of the web — so why does creating a “React app” produce an empty HTML file? Why are we not taking advantage of the most basic feature of the web—the ability to see content quickly before all the interactive code loads?”

The answer has been Server-Side Rendering the initial page of a SPA, but this isn’t a free win. This approach improves First Contentful Paint but comes with its own cost in Time to Interactive and First Input Delay. The user can see the interface relatively quickly, but if they click something, nothing happens. Ryan Carniato, creator of Solid JS, has written about Why Efficient Hydration in JavaScript Frameworks is so Challenging.

Sacha Greif has written of his disillusionment with SPAs:

“While I’ve always been bothered by the downsides of SPAs, I always thought the gap would be bridged sooner or later, and that performance concerns would eventually vanish thanks to things like code splitting, tree shaking, or SSR. But ten years later, many of these issues remain. Many SPA bundles are still bloated with too many dependencies, hydration is still slow.”

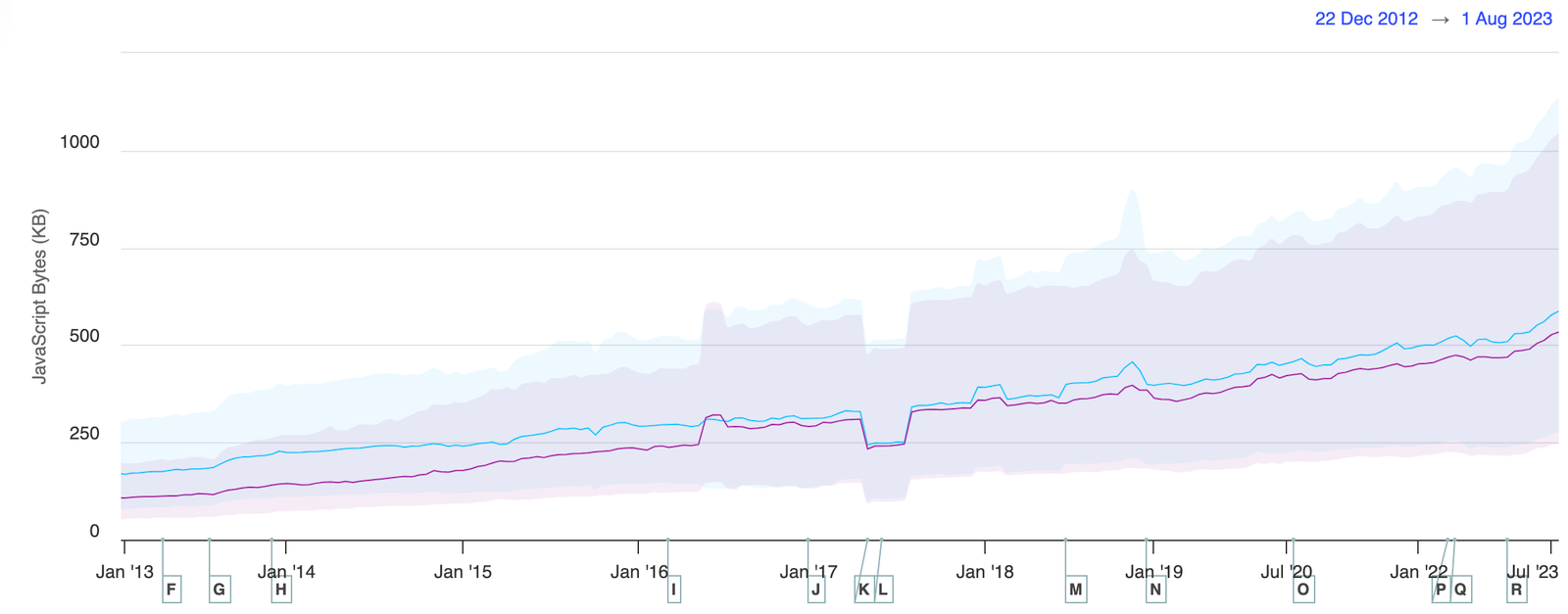

Perhaps the biggest issue isn’t client-side routing itself but the NPM-driven development style dominant within that architecture where a smorgasbord of dependencies (Styled Components/Emotion, Apollo/Redux, form libraries, UI component libraries…) gets installed. While seemingly every release of a frontend framework markets itself as “blazingly fast”, the size of JavaScript bundles has only continued to grow over time. Between 2021 and 2022, the amount of JavaScript shipped to browsers increased by 8%, even as new features in JavaScript, HTML, CSS make it easier to avoid writing mountains of script. Here’s what growth looks like from 2013 — a steady increase:

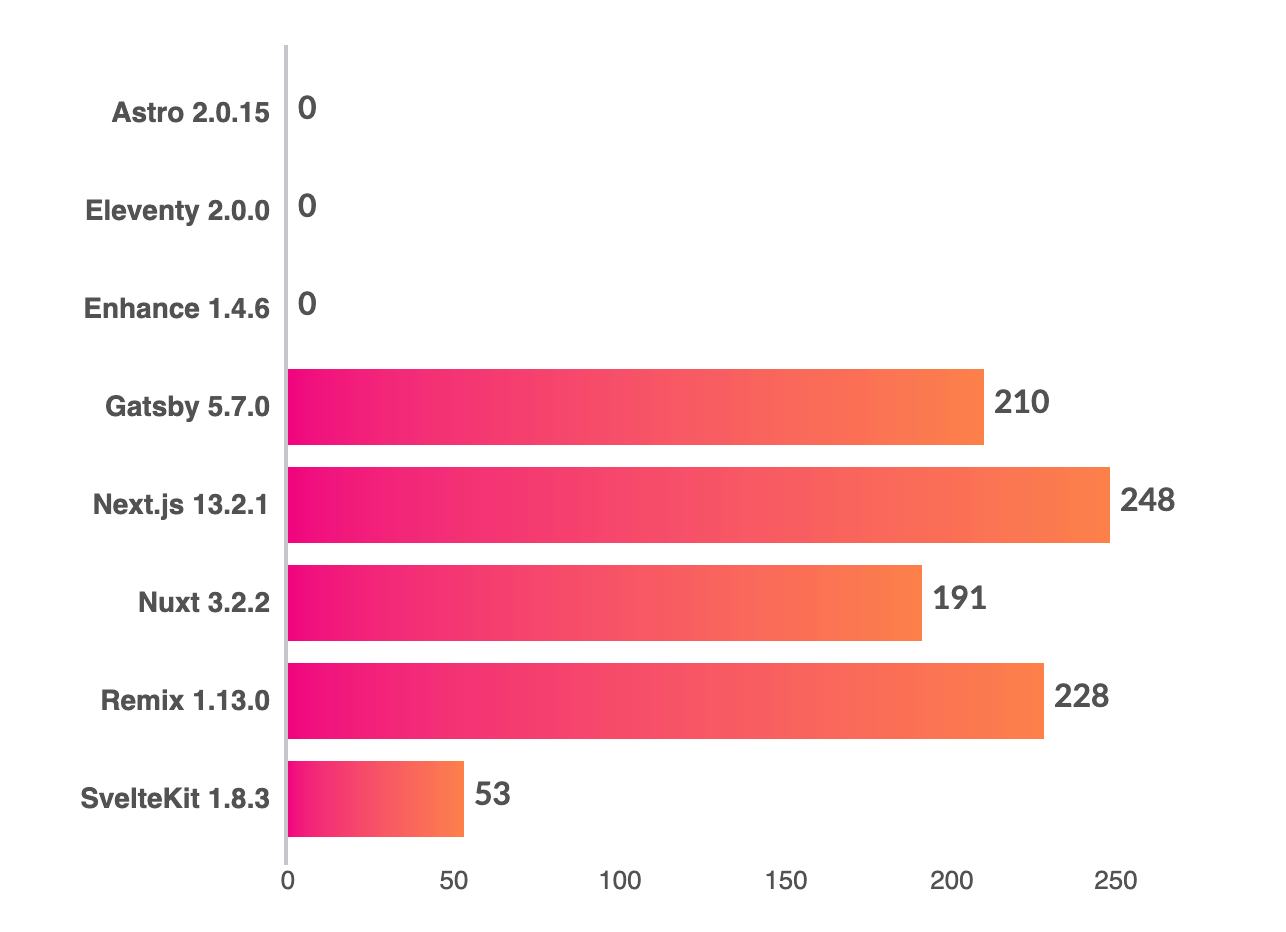

Zach Leatherman created the following chart showing the weight of JavaScript sent to the browser by various static site generators and frontend meta-frameworks (measured in kilobytes of uncompressed resource size):

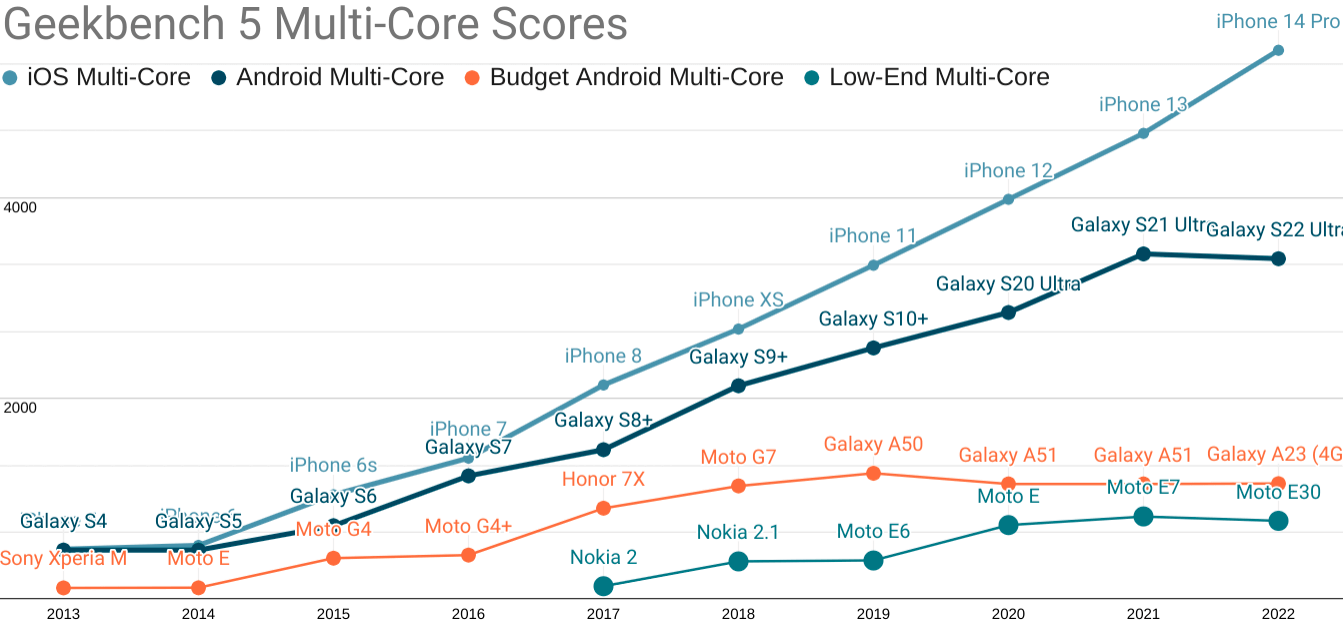

Meanwhile, as pointed out (repeatedly) by Alex Russell, the mobile CPUs of mid-tier Android devices have plateaued. There is an increasing chasm between iPhones and cheap Android phones.

Problems with SPAs

Memory leaks

Nolan Lawson is the creator of Fuite, a CLI tool for analysing memory leaks. He tested Fuite on the home page of ten popular frontend frameworks and found memory leaks in all of them:

“Somewhat surprisingly, the “basic” scenario of clicking internal links and pressing the back button is enough to find memory leaks in many SPAs”.

In Multi-Page Applications the browser clears memory on every navigation so memory leaks are almost never a concern.

SPAs aren’t great for SEO

Google take Core Web Vitals into account when ranking your site within search results. On web.dev (a blog run by Google), the answer to the question “Do Core Web Vitals metrics include SPA route transitions?” is a clear “no”:

“Each of the Core Web Vitals metrics is measured relative to the current, top-level page navigation. If a page dynamically loads new content and updates the URL of the page in the address bar, it will have no effect on how the Core Web Vitals metrics are measured.”

In Single Page Applications, a trade-off is made: subsequent page loads are optimised at the expense of a slow initial page load. With the way Google currently measures Core Web Vitals, the first page view is all that counts. The web.dev article concludes “properly optimized MPAs do have some advantages in meeting the Core Web Vitals thresholds that SPAs currently do not”. Google is investigating ways to make these metrics fairer.

Problems with MPAs

Evaluating JavaScript on every navigation

In a multi-page website, all scripts, including bulky third-party scripts like analytics, are evaluated every time a user navigates to another page.

Persistent UI and managing state

In a SPA, video and audio can play uninterrupted between navigations. Or take the example of a scrollable sidebar. If the user scrolls down and clicks a link, the position of the scrollbar will persist on the next page. If you want an element (e.g. an audio or video player, a sidebar, a chat widget, a iframe) to persist between pages without losing state, you need client-side routing.

Astro, a framework that has proudly focused on MPAs, recently added a SPA mode to cater to this use case: there’s currently no way to get past this issue without client-side routing.

HTML-centric Development

For many, MPAs are associated with sprinkling jQuery onto server-side templating languages like Handlebars. Plenty of HTML-first options have emerged over recent years. There’s Petite Vue from Evan You, Stimulus from the creators of Ruby on Rails (but not tied to any particular tech stack), Enhance, HTMX, and Alpine JS.

Here’s how Stimulus markets itself: “It doesn’t seek to take over your entire front-end—in fact, it’s not concerned with rendering HTML at all. Instead, it’s designed to augment your HTML with just enough behavior to make it shine.” Stimulus was used to create the email client Hey and the project management tool Basecamp. They’re the sort of highly-interactive experience one would usually associate with SPA, but they both deliver a good user experience. Compared to the popularity of frameworks like React and Vue, none of the above mentioned projects have gained significant traction. Theres also web components (and tools for building them, like Lit and Stencil) but they’re still something of a work in progress.

Marko, Astro, Fresh and Qwik are the most interesting MPA-focused frameworks. Dylan Piercey, from the Marko team at eBay, sees increasing innovation in this space:

“It bothers me that many people in the “MPA” vs “SPA” debate see MPA’s as the “old guard” or some kind of legacy tech. The push I see is a renaissance of MPA architecture that leverages it’s unique strengths and blurs the line with SPA’s.”

Tools like Marko and Astro are an attempt to provide a modern developer experience while delivering peak MPA performance.

Conclusion

Is the current terminology still fit for purpose? Ryan Carniato has spoken of the “dawn of a new type of architecture”: “Resumability, hybrid routing, partial hydration, RSCs, are all efforts to close the SPA/MPA divide.” What was once a clear distinction between MPA and SPA is becoming far more blurry. Dan Abramov positions React Server Components between the two:

“Is App Router an MPA or an SPA? Neither quite makes sense. Its navigations aren’t page reloads. State preserved. So that doesn’t seem like an MPA. But it can pregenerate HTML (and navigation payload) for routes, kinda like MPA. You write code in req/response model like MPA.”

Regardless of technological advancements in browsers and frameworks, I doubt the fundamental trade-offs will change:

-

Building a content site (a marketing site, a portfolio, a blog, etc) or a site that needs to work well on mid-range mobile devices? Worried about bounce rates? Are users coming to your site for a short space of time? Send static HTML and optimize page load speed and bundle size. Even Tanner Linsley, a prominent contributor to the React ecosystem, has tweeted about the joy of moving a marketing site from React to Wordpress.

-

Building a highly interactive web application that users keep open all day? Does it primarily target desktop/laptop or high-end mobile devices? It can be a SPA.

While SPAs long felt like the future, some of the biggest sites on the web (Amazon, eBay, Wikipedia) were wise enough to keep their routing and rendering on the server.